By 1980, with a growing acceptance of my own sexuality, I’d more or less come to the decision that i was going to pursue a career as an artist of the male nude. Over time, as I got clearer about it and more committed, I also got clearer that i wanted to improve my drawing skills.

I had some natural talent but I was starting to see that that wasn’t enough and I needed to work on my technique. With my focus on the male figure, I knew I needed to improve my knowledge of anatomy. I wanted to be able to draw the figure more fluidly, and to be able to draw it from any angle, in any position.

Everything I read told me that I must draw every day, so I decided I would do my best to make drawing a regular part of my routine. But what was I doing to draw? I had some books on anatomy for the artist, but drawing from those same illustrations over and over again got boring pretty fast.

This was at the beginning of my career and I still hadn’t worked with that many models, which meant I had a very limited amount of photographic reference material. (I never had much interest in working from a live model—too much trouble, too expensive, light always changing, model moving too much, etc.—so I was always more interested in working from photos.)

I found some reference material in gay skin mags, but that was pretty limiting, with a fairly narrow range of stereotypical poses. However, this was in the days of VHS machines, so occasionally I would find something useful on TV that I could tape—the example that comes to mind most clearly is a documentary on a tribe in Africa, with lots of shots of nearly naked Black men throwing spears, dancing, and staging ritual battles. This was terrific material for somebody learning to draw the male nude. I videotaped it, then played it back with lots of freeze-frames so that i could do quick sketches. I had a small library of recorded videos, and I learned a lot this way. But it was still pretty limited.

But my options improved as I got more experienced and worked with more models. My sketching practice helped define the photo shoots, too, since I had in mind the kinds of interesting poses that would be a challenge for me to draw, so I would do my best to direct the model in a way that would give me those kinds of poses—lots of unguarded, natural poses, lots of moving around, etc. To this day this still pretty much defines my approach to photo shoots.

I never really thought of myself as a photographer—photography was just what I needed to do to get material to draw and paint from. But by necessity I learned a bit about photography, and it was pretty different in those pre-digital days of film cameras.

One of the first things I learned was that shooting regular negative film and ending up with small photographic prints (the kind of photos we now see mostly in old photo albums) was less than satisfactory. The negatives themselves were sharp and high-resolution, but the prints you got back from the drugstore were pretty low quality, and expensive too. The alternative was a professional studio where you could get large high-quality prints, but that was even more expensive and not very practical.

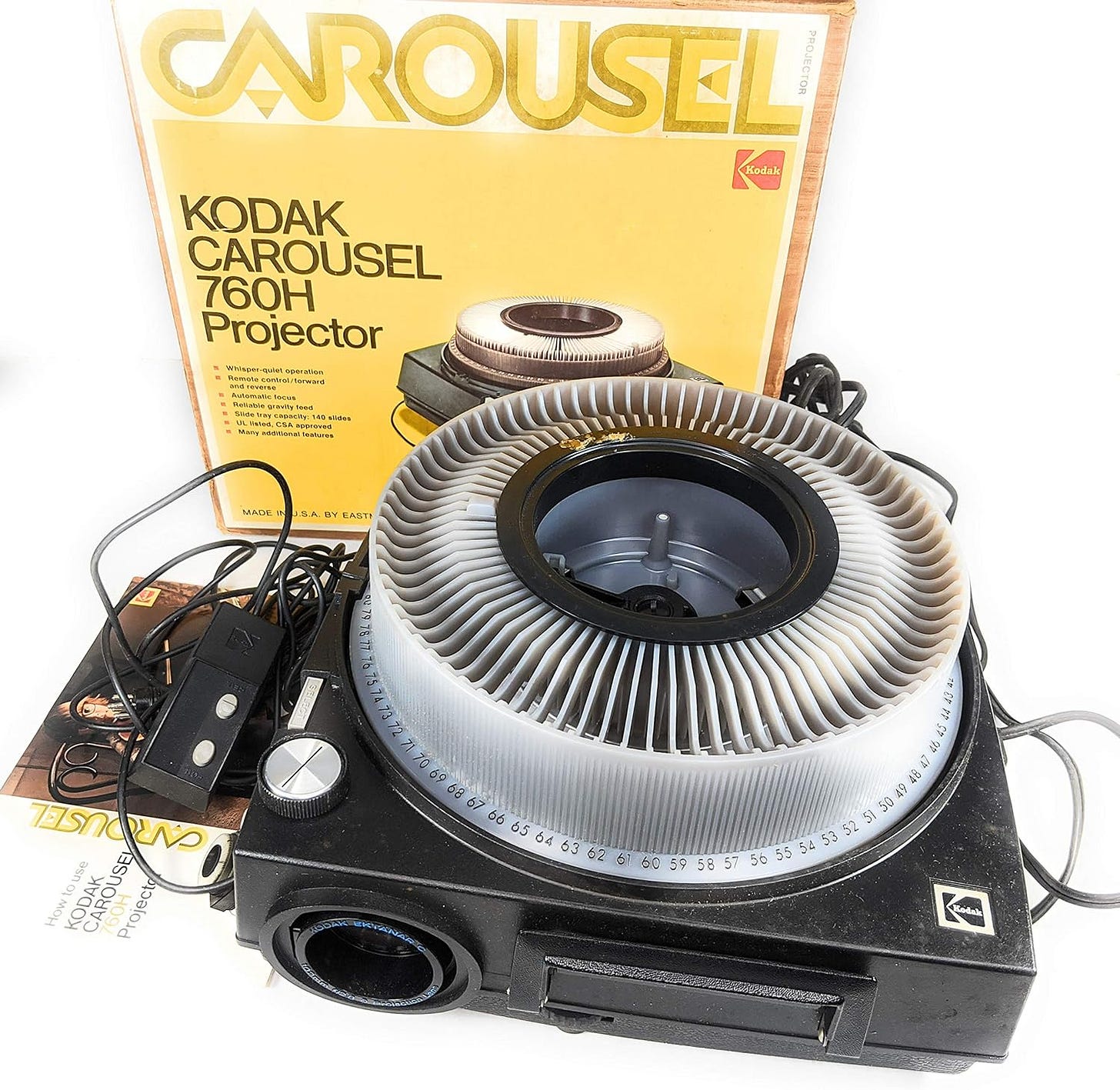

I found a workaround, however. I remembered how, when I was a kid, my parents shot a lot of 35mm slides, so I thought I’d give that a try. I got some 35mm slide film and bought a used Kodak slide projector, and the next time I had access to a model, I shot slide film.

This turned out to be a great solution. With the slide projector and a blank wall, I could blow the images up and see as much detail as I wanted. Slide film is just like regular film except it delivers a positive image instead of a negative one—so not only do you not need to make a print, the image you’re projecting is the actual original image the camera burned into the film, so you’re not losing any resolution. On top of that, the cost of slides was much less than prints!

(Slides were good for another reason too. In those days if you gave the photo-processing studio anything with nudity, there was a chance they would (a) refuse to print it, or (b) destroy it without bothering to ask you. With slides, there was less chance of that, because there was no printing involved, just film processing, and it was a lot harder to make out what was going on in the image.)

With the slides and the projector, I now had a great setup for my sketching practice. The projector was a Kodak Carousel, which meant that you loaded up the slides in a circular magazine, then advanced them one at a time as you projected them on the screen (or wall).

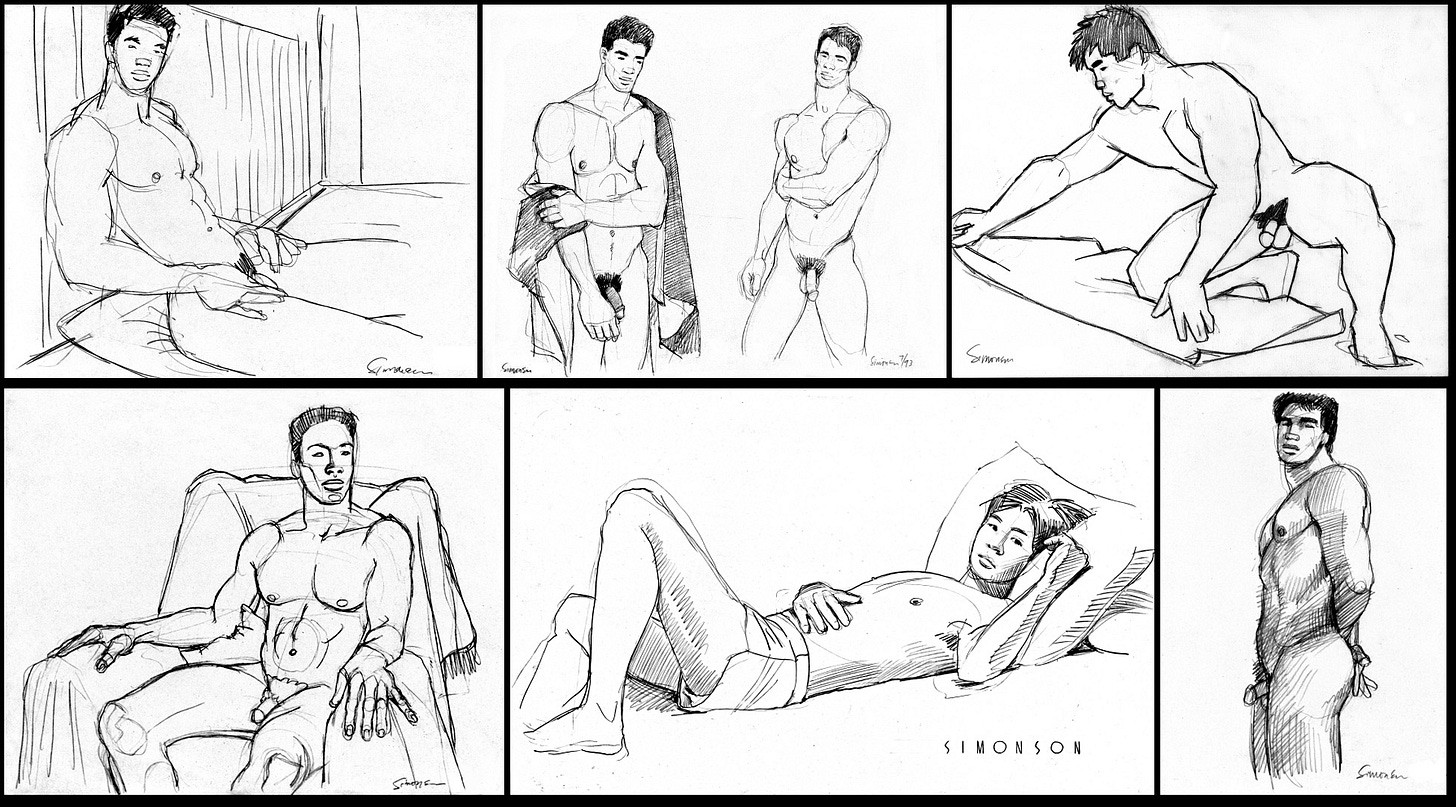

A roll of film had 36 exposures, so what I got back from the Kodak lab was a yellow box with 36 slides inside. That matched the size of the carousel, so I could load up one entire box of slides in the slide projector, aim it at the wall, then sit at a table or easel with my paper and pencils and sketch each slide as it came up. I sometimes limited myself to 2 or 3 minutes per sketch—or even 1 minute. As I finished a sketch, I advanced the projector to the next slide, and drew that. Whatever image came up, I drew it. I found I improved faster when I drew more, so I wanted to draw as many sketches as quickly as I could.

This was a great way of improving my technique, my confidence, and my overall knowledge of male anatomy. It was a slow process, but I gradually started to see a positive difference in my finished works, both drawings and paintings.

Surprisingly, I actually got more useful knowledge from books on cartooning than I got from the standard artist’s anatomy references.

One of the best was Jack Hamm’s Cartooning the Head and Figure. He had a section on drawing for the sports page (the book was written at a time when illustrators could still make a living drawing editorial content for newspapers and magazines) which I found really helpful. The way he used a few simple forms to create an athletic male figure was a revelation for me.

Another extremely useful reference was the book How to Draw Comics the Marvel Way. This book taught me how to use artful exaggeration put more life and energy into my figures.

All the references I found and used were helpful, but the real progress happened because I committed myself to making a habit of drawing often. I didn’t buy sketchbooks because I didn’t want to spend that much on drawings I would be throwing away. So I bought reams of typing paper and drew on that. And as I said, most of them were thrown away. In those early days I didn’t think much of my drawing efforts so I rarely kept any of them.

But my rough sketches gradually began to improve.

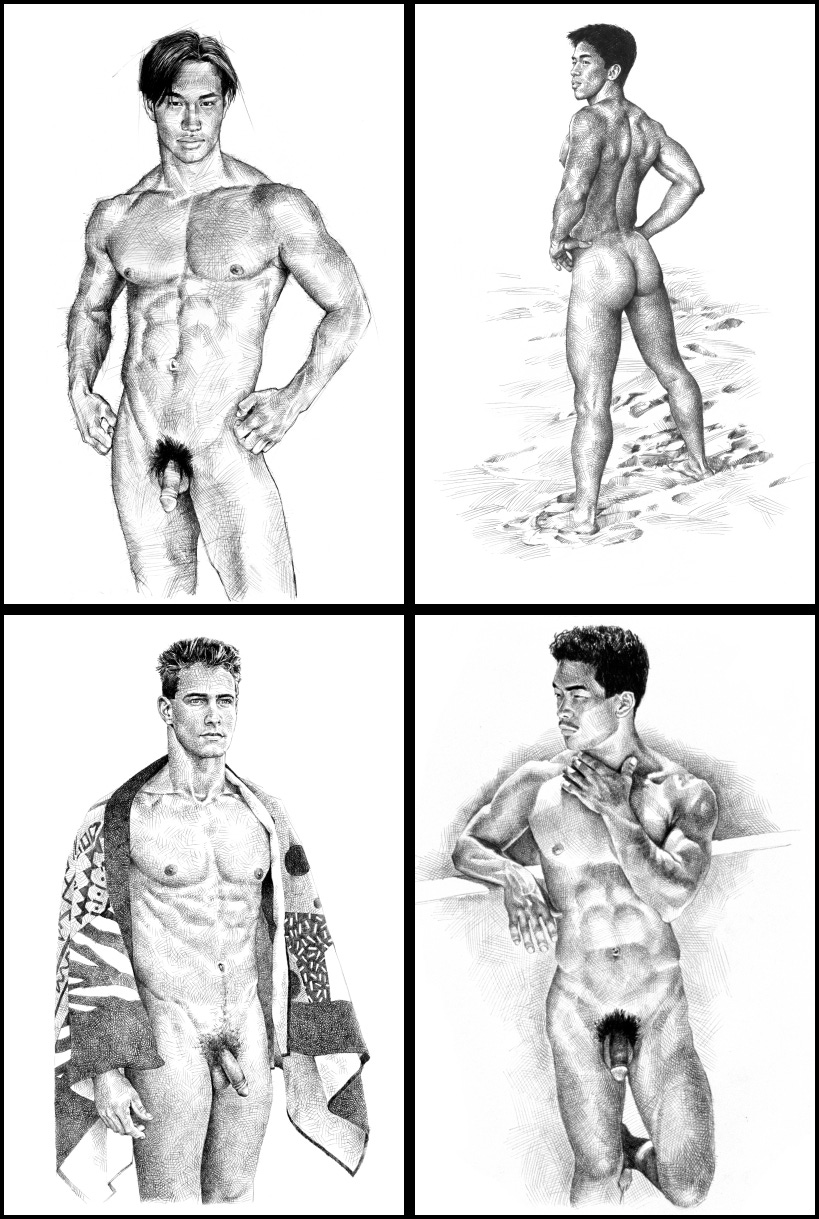

I already had a growing collectorship for my crosshatched drawings. These were quite different from the rough sketches that resulted from my drawing practice—they were very realistic, highly detailed pencil drawings that had very little of the spontaneous energy of my sketches. In those days I still didn’t put much value on my rough sketches, so it was a surprise when one day as I was showing a collector my newest paintings and crosshatched drawings, he happened to see a pile of my rough sketches, and expressed interest in them. In fact, he wanted to buy some of them!

I didn’t even know what price to put on them—I think I sold them to him for $25 each. But it was a watershed moment, as I realized that I needed to change my attitude about my rough sketches. They were actually saleable art!

It became easier to maintain my sketching routine now that I knew I was creating something that I could sell. At the same time, it became a challenge to maintain my detachment from the business aspect so that I could continue to lose myself in the act of drawing. I was still a harsh judge of my own efforts, however, and I would usually throw away 80-90% of my output.

Just the same, I produced a lot of rough sketches, and starting in the late 1980s, I made them an important component of the body of work I shared with the world. I started cataloguing all my artwork right from the start of my career, so I can tell you how many rough sketches I’ve deemed worthy of offering to my collectors over the years—the total is a bit under 6,500 (I’ve probably sold at least 5,000 of those). Keeping in mind the ‘good enough’ sketches were 10% or less of my total sketching output, I figure I’ve done, at a bare minimum, 70,000 sketches in my career so far. That’s a lot of drawing.

And it’s paid off. Now I’m in my early 70s and I’m often pleasantly surprised at how easily a sketch flows out of me. But we also need to note that my percentage of ‘keepers’ from a typical drawing session is still 20% or less. Which means I’ve improved a lot, but the challenges are still great. That’s one of the things I like about the career I’ve chosen, by the way—I never get bored because the challenges never go away.

These days it’s a lot easier to access reference material to draw from. I have a ton of images on my computer and can cycle through them much more easily than I could with slides and a projector. But I still follow the same routine, loading up a folder of images and then cycling through them one by one, drawing whatever comes up. I still have not found a better way to keep my artistic flow going and growing.

If you’re an artist, aspiring or established, I hope you’ve found my sketching history interesting and maybe even helpful. There’s no shortcut to improving your proficiency as an artist, and that’s a good thing. Because, and I think most of us need this reminder, the goal is not to become a great artist and produce great works. The goal is to lose ourselves in the moment, in the act of creating. (And that attitude is a lot more likely to produce great art.)

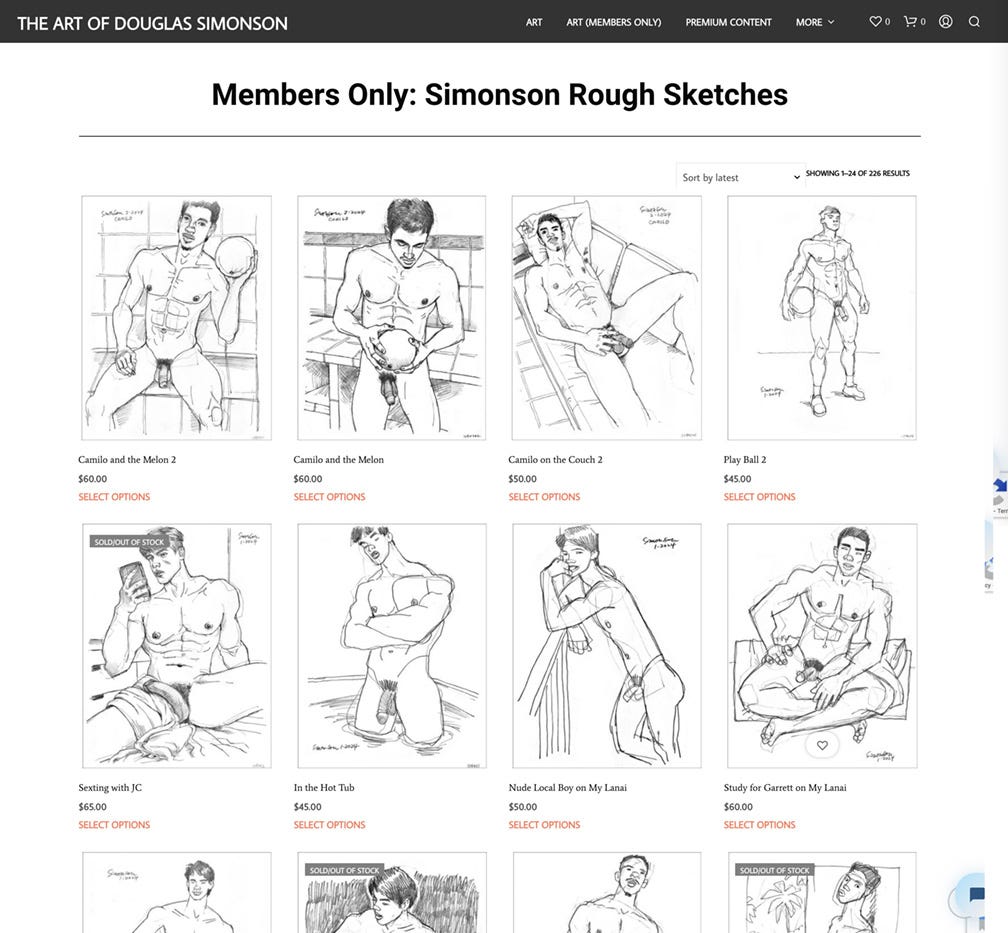

P.S. If you’ve read this far, you may be interested in viewing more of my rough sketches. That’s easy to do by visiting my website at douglassimonson.com, where you’ll find over 400 still-available rough sketches. Most are priced at $60 or less. There’s also a section of my website called the Simonson Archives (available only to paid subscribers) where you can see hundreds of early works which had previously only been seen by myself and the collector who purchased them.

Thanks for reading!